|

I’m writing about a county lines drug dealer. My agent has not been sure. ‘Why are you writing about county lines? Why aren’t you writing something closer to your own concerns and experience?’

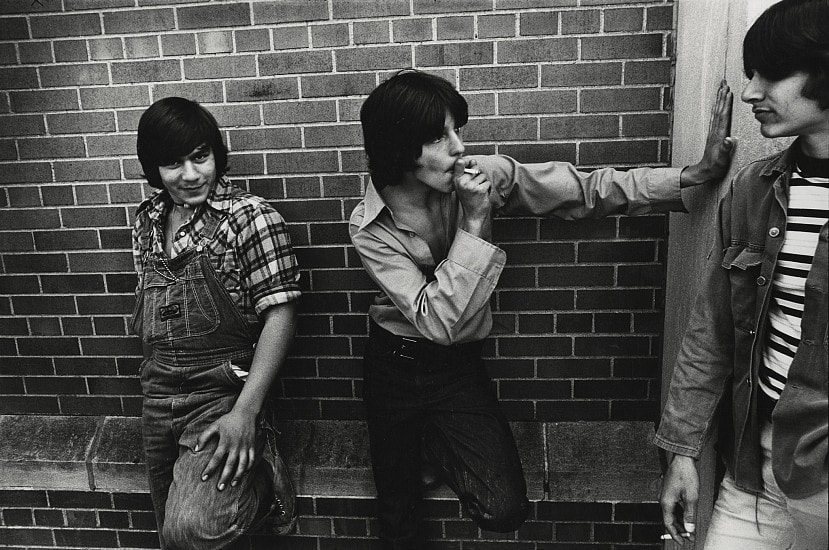

Good point, I thought. I’m not writing from the point of view of the young drug mule, but it still seems kind of a stretch for me, a middle-aged university lecturer in a small market town, to be writing something with these issues. But I couldn’t stop writing it. I really like it – love my Cathedral Chorister narrator/heroine and her musical family. I love her new friend Mike and her old friends Hannah and Angie. I also love the young drug dealer who Harriet tries to help. So, I’ve been secretly typing away. Then I watched the Peter Jackson Beatles documentary, ‘Get Back,’ and the songs reminded me of something I’d nearly forgotten. When Abbey Road came out in 1971, I was eleven years old. It was right in the middle of my father’s two year stint as Head of Juvenile Narcotics in the Kansas City, Kansas police department. Back then, just like now in the UK, young people were used to move drugs around. They’d have money and drugs in their pockets and the actual dealers would stay clean and just collect from them… these kids had been young roadmen. My father’s idea for how to help the local roadmen was to bring them home. Our house became their refuge. We had five or six regular roadmen visitors. Mom would feed them and do their laundry. I’d do my homework and help them with theirs, if they’d managed to go to school that week. They played with the dog. They watched our television with us. They took showers. They were just… there. When I got my period, age 12, I had to tell one of them at the same time I told my mom, because the two of them had been in the same room, listening to records together, and my mother hadn’t want to stop. One of these kids bought me the Abbey Road album when it came out, and my favourite song became Maxwell’s Silver Hammer. Hearing this song coming together in the Get Back documentary brought that time completely back to me. My subconscious, creative mind had never forgotten. Mike, Denny and the other boys were all still there somewhere in my head, as present as they’d been when I made them stove-top popcorn or baked them cookies. I’d used my knowledge of them and their concerns to make my young county lines victim, Courtney… had drawn him as a composite of the boys I’d known when I was twelve years old myself. I now have to write my agent and say, ‘Well, actually, I figured out why I wanted to write this so badly.’ It’s strange isn’t it, what fiction does for writers. I’ve had a disjointed life, where things often ended abruptly and people and places got left totally behind. I think when I write stories, I stitch the world back together again – for me, and for my young readers. Even though I couldn’t actually articulate it – it was my story, after all.

3 Comments

It’s eight-thirty on a Friday morning and I’m putting on makeup. I’ve only had two or three hours of sleep and I’ve got huge dark circles under my eyes.

I hadn’t been having fun. My daughter had a health crisis and needed to come from university to our local doctor’s surgery, so I jumped in our new-to-us electric car and began to motor down. I dropped everything and focussed on that one, important thing. I’m good at that. I’m good at taking decisive action. I’m good at coming up with creative solutions to problems – frighteningly, startlingly good. I’m good at making conceptual leaps. I’m good at doing extraordinary amounts of work to a fairly high standard. I’m good at keeping up varied interests. I’m good at shutting out the entire world while I read a book. And these strengths have given me an enviable career, as an author and as an academic. I have been able to contribute to society, contribute more than anyone who knew me as a child might ever have thought possible. But I’m not good at other things. I’ve recently discovered why. I have ADHD. I’ve had it all my life, and I’ve had all the problems that go along with it. Problems maintaining interest and focus on repetitive tasks. Problems with not speaking when I’m not meant to speak. Problems with breaking off interesting conversations to get back to work. Problems in keeping my house clean, my bank account balanced. Problems in remembering birthdays, appointments, meetings, deadlines, emails that need an answer. Problems with anxiety over all of the above problems. I’m also dyspraxic, even as an adult, although my trips to A&E (for say, walking through a glass door or dropping a large jar on my head or tumbling into a ditch when out on a run) are, thankfully, over. I’m dyscalculic. I spend a great deal of time checking and rechecking numbers during marking and banking, but this doesn’t help with my administrative and financial skills. When stressed, even simple addition can be a struggle. The dyscalculia also gives me problems with spatial relationships, making navigation challenging. Which is why, on Thursday night, I found myself on a remote country lane, trying to follow directions to a car charger. I went up and down the lane, first with the sat nav, then with Google maps, then with Apple maps. I finally tried to just drive to the motorway to get to it, and ran out of juice a quarter of a mile from my goal. It had been cold and raining and a number of other people’s mistakes meant that I spent seven hours – first on the hard shoulder, then in the doorway of a nearly-shut motorway services. Finally underway, an accident on the M4 added another hour to my journey home. By that time, my daughter had taken the train, been collected by my husband, and had been in bed for hours. Now, on Friday morning, I stand with the concealer in my hand. I’ve managed to cover up or excuse my problems fitting into neurotypical life for a great many years. But sometimes, you know, there’s just not enough concealer in all the world. |

Archives

February 2022

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed