|

Some things are true. Two plus two are four. The earth is warming due to the use of fossil fuels. Invasion and colonialism founded much of European wealth. Concepts of race arose to justify invasion, colonialism and the violent exploitation of some people.

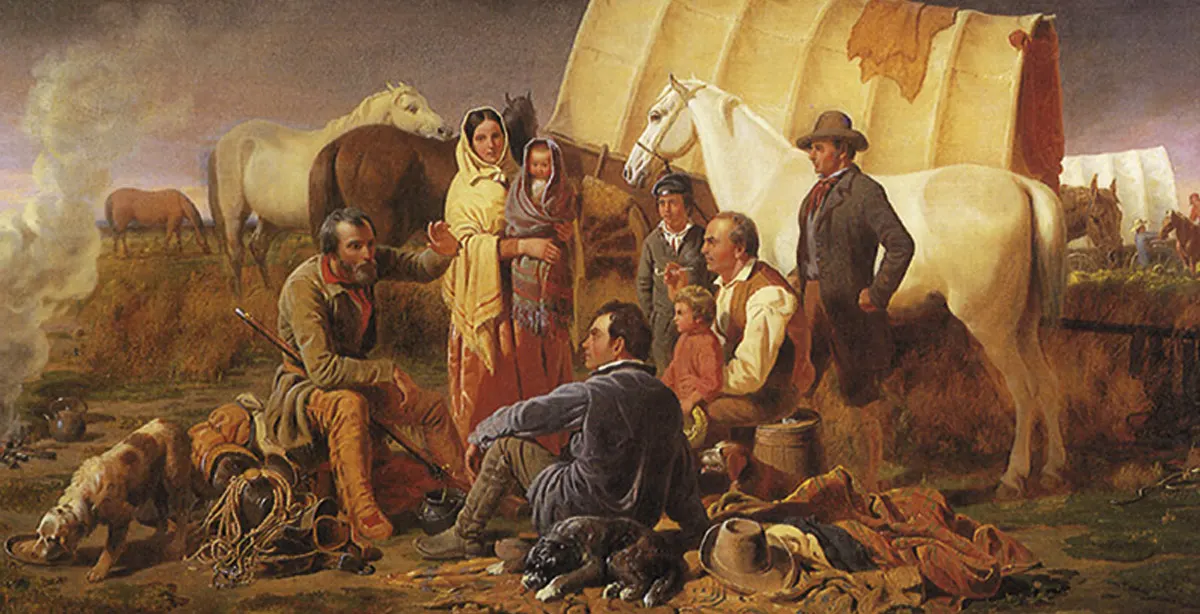

When we don’t teach children the truth about any of these things, we do them no favours. I know this, because I was a child who was not taught about invasion and colonialism, and so was my short-term-stepbrother, who I’ll call J. It was odd not to be taught about invasion and colonialism as a child living in Kansas – land that had been obviously invaded and colonialised two generations previously. We celebrated Thanksgiving, when the pilgrims thanked the First Nation people for saving them from starvation. At school, we glimpsed other First Nations people in The Deerslayer and ‘Hiawatha’ and stories of Sacajawea and Pocahontas. At home, in films and on television, we watched horrible bands of savages murder brave pioneers and cowboys. The pioneers and cowboys were us, Americans. Noone had to explain the logic of confining horrible bands of savages to reservations: in fact, I felt quite relieved that this had been done. A bright child could, however, see holes in this narrative. How did Hiawatha and Sacajawea turn into ravening hordes of killers? The adults at school and home had a standard answer for this enquiry. These people had been from different tribes. It was the Apache, Commanche, Cherokee and Sioux who had caused all the ruckus. We had two Cherokee boys in our class and one went ‘home’ to the reservation every holiday to spend it with his grandfather, learning the ‘old ways’. Robbie was not reticent about the omissions of our education, and told us about the forcible relocation of his tribe known as the Trail of Tears. I also noticed that some television shows and films presented alternate views about tribal uprisings – and even about our right to take tribal lands. Learning about the great buffalo slaughter convinced me that the settlers had not really been the good guys. In the end, the only way we could defeat the tribes’ light calvary was to cut off their food supply, and this was clearly despicable. Although my great-grandparents had participated in the Oklahoma Land Rush, I began to feel my heritage wasn’t wholly desirable. I knew what hunters were like – in my family, you got a BB gun at eight, a bird gun at ten and your first deer rifle at twelve. I knew when trophy hunting or hunting for the pot turned into slaughter. I’d seen it first-hand. I could easily imagine the buffalo slaughter. And so, around the age of ten, I turned a jaundiced eye on the ‘balanced’ learning of my childhood. ‘J' was different. J had not grown up in my family. I acquired him when I was seventeen, his brother was fifteen and J was thirteen. We were all children of messy 1970s divorces, and J was particularly troubled by the two different versions supplied to him about the end of his parents’ marriage. He liked to sit on the roof and smoke pot. When I joined him there, he would complain about everyone having their own ‘reality’. He just wanted to know what was true, who to believe. It was a time when the culture wars were fought with bullets: all the heroes of my youth had been assassinated, as had some of the young people protesting the Vietnam War at Kent State University. Misinformation and disinformation did not suddenly appear with social media; the whole tawdry Watergate saga played out in our living rooms, where we had previously watched nightly body count reports from Vietnam, and heard about the brave freedom fighters of the IRA. J hungered for the truth. He didn’t care if it hurt – he just wanted to know. But much of the truth was kept from us – about our parents’ marriages, about how newspapers and media concealed as much information as they revealed, about how the world actually worked. We certainly hadn’t been told how we came to be sitting on the roof of a house on the prairie, where buffalo had, until a little over a century ago, wandered in their hundreds of thousands. J and I lost touch after our parents – inevitably – divorced. I saw him occasionally, until his grandmother and auntie died, and then didn’t see him at all. We caught up twenty years ago on Facebook, and I went to see him. He had found certainty in Christ, and was bringing up his children, including a boy with Downs Syndrome. He was working in his father’s line of work, trying to do things his dad’s way, having finally decided who had been right and who wrong in his parents’ marriage. Of course, he became a Trump supporter. The same hunger for certainty that had taken him further down the line from religion to fundamentalism took him to the red hat. I could hear him on the roof, night after night, saying that he, ‘just wanted to know what to believe.’ Now he had what he wanted – someone was telling him what to believe, was giving him the certainty he had always craved. He disappeared off Facebook around the time my visits home became more about trying to arrange care for my mother than seeking out friends and acquaintances. After Trump’s defeat, he came back onto the site. He’s just posted a photo of young Hitler without comment. Hitler looks glowing in the enhanced photo – his eyes sparkle as he faces the future, although they also seem unfocused. Like Adolph, I’m looking at the future. Like him, too, I’m from the past – the amazing link you become if you live past fifty. I remember the pain – and the loneliness – of uncovering the genocide in my heritage bit by bit. I learned why my grandmother prayed a decade of her daily rosary for the Cherokee nation, why she donated money, why she had a wooden ornament on her wall commemorating the Trail of Tears. My colonial heritage slowly, agonisingly, became evident to me with horrible feelings of shame that have not helped me to deal with racism in general. Shame comes from secrecy – if we acknowledge these things together, bear them together, it’s much easier. Also, children hunger for the truth. Without it, they are vulnerable to whoever offers them certainty. I fear for J, and I fear him, too. I fear for us all if we don’t teach our children the truth about our colonial past. Advice on the Prairie was painted by William Tylee Ranney

0 Comments

|

Archives

February 2022

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed